How Culture Works

"DOES EVERYTHING ALWAYS HAVE TO BE ASSESSED?" No. But when cultural work is financed with public funds, there is a necessity to evaluate.

Prague Permanent linkThe Shared Cities Atlas maps current sharing trends in Central and Eastern European cities. How does the Shared Cities Atlas use data to visualize its stories? And which initiatives or new forms of sharing in the region are the most remarkable ones? Find the answers in the interview with the editor of the Shared Cities Atlas, Helena Doudová from Prague, Czech Republic.

© Petra Hajská

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

By Martina Peachment Brehmer

The Shared Cities Atlas maps current sharing trends in Central and Eastern European cities. Which initiatives or new forms of sharing in the region are the most remarkable ones?

The Atlas presents best practices which were created as part of the Shared Cities: Creative Momentum project. We commissioned our partners to develop case studies which deal with sharing in general – in public space, in the digital realm. I’d like to highlight Belgrade with its urban hubs and participatory models of sharing in the city. Our partner Medialab in Katowice used data stories to visualize information in the Atlas as well as ran its own project analysing data on culture in the city, like the accessibility of cultural institutions. The trend of sharing knowledge and sharing data is important for new and innovative sharing practices. Data has also become a commodity. Also, the new digital reality has brought about new digital platforms that started as sharing platforms – like Airbnb or Uber – which then became profit-oriented. First, they used a bottom-up model but then became global – this new form is called “platform capitalism” in literature. In the Atlas, we introduce other sharing initiatives not focusing on the capitalization or commodification of data but rather promoting open access to data – like showing municipalities how to make data accessible to citizens.

How does the Shared Cities Atlas use data to visualize its stories?

Data is one of the layers of information the Atlas presents. In “Shared Cities in Data” we compare Central European cities based on their population, economic and spatial development or mobility. The Atlas is structured around seven cities – Berlin, Prague, Belgrade, Bratislava, Katowice, Budapest and Warsaw while we also use international benchmarking with European cities like Amsterdam, London or Athens. Each of our seven cities is captured in a “City Profile” in data. A special chapter is devoted to “Sharing Data and Knowledge” and also in every city data stories highlight trends like the affordability of neighbourhoods, digital platforms for citizens’ participation – like the “Message for the Mayor” app used in Slovakia or data surveys of female participation in Belgrade. Further layers of the Atlas are the visual narrative of “Photography Essays” for which we commissioned a photographer to travel through post-socialist cities to capture public urban spaces and thematic chapters “Sharing Spaces and Architecture“, “Urban Activism” and the already mentioned “Sharing Data and Knowledge.

© Jan Faukner

A hot topic today is the affordability of cities – what trends does the Atlas capture when it comes to living costs in the seven Shared Cities – from Berlin to Belgrade?

The Atlas has an entire page devoted to economic trends, housing and lifestyle indicators like the cost of going to the cinema, buying a bus ticket etc. In housing statistics, the interesting figure is how much of a household income is taken up by housing costs. This is a good indicator of a general quality of living. In Berlin, in spite of a large number of one-person households, the area inhabited per person remains high with an average of 45 m2. As income is relatively high with over 2000 EUR per month, housing costs remain relatively affordable in the city – taking up about a third of a person’s income. In contrast in Belgrade, with an average income of ca. 800 EUR, the rent of a 3-bedroom apartment of 600 EUR in the city centre is more difficult to manage. In Prague, rent a flat in the city centre for 1100 EUR takes up about 50% of a household’s income. The figures serve as a median orientation as individual factors come into play – family property, different rental contracts, multi-generation households.

Would you say that the attitude in the region towards open data is different compared to Western European cities?

Central Europe is catching up quickly. In terms of sharing data this kind of regional divide is not an issue, the digital divide runs actually between the global north, which Central Europe is part of, and the global south. We see new apps for mobility, public use of space or sharing objects launched daily in the region. Where I do see a difference, however, is a smaller concern about data privacy than let’s say in Germany. The EU has a single policy, so data privacy rules are the same across its member states. There is, however, a difference in the public discussion. In Germany people don’t like to share their personal information – like their house numbers – on Google Street View, whereas this isn’t of great concern in the Czech Republic.

Do citizens have a right to the city and its resources?

This question has been addressed by different scholars – public space has become a contested point in the academic as well as activist discourse. The writer Henri Lefebvre coined the term “right to the city”, then there was Elinor Ostrom speaking about common resources and particular resources in cities – resources which can be divided, which are tangible and limited like fossil fuels, coal but also water or air. Other resources that are not tangible and don’t have to be divided as they are not limited – like knowledge or creativity. When you share something you have to divide something at the same time. How you share and divide common goods is a process of social negotiation. It’s important to have good arguments so that the city can be shared amongst the majority of people who live in it, not just amongst the privileged ones.

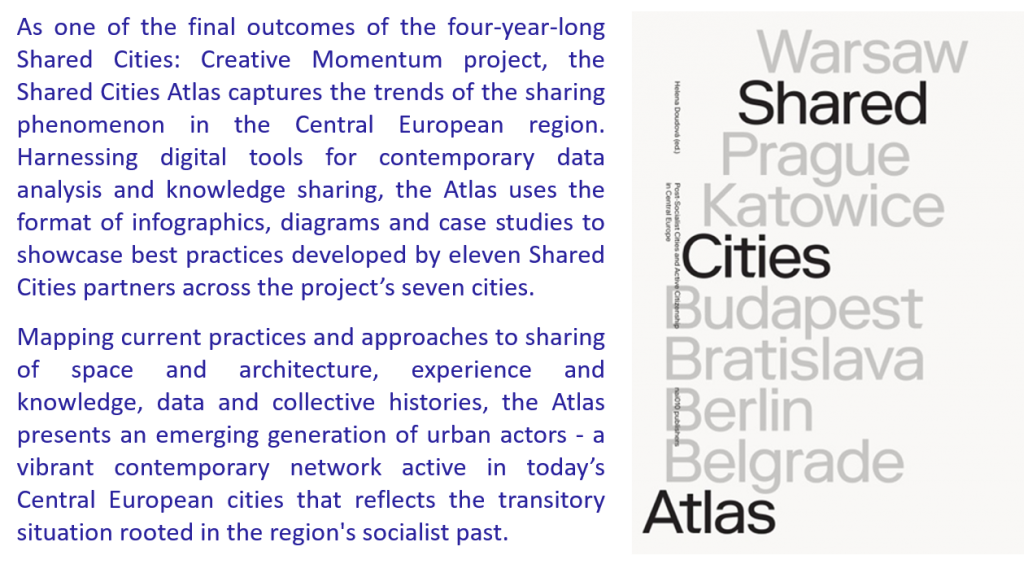

© nai010 publishers

What is the new global sharing paradigm in architecture and the public sphere that the Shared Cities Atlas aims to capture?

There are different views on sharing. It is usually associated with Airbnb and Uber, which is not the way we see it. We sort of redefined this new global sharing paradigm in terms of Duncan McLaren and Julian Agyeman. In their book “Sharing Cities” they point out that the emphasis lies on the right to re-make the city as a form of an urban social contract with a specific critical or creative agenda. In the Atlas, we present creative forms of sharing driven by idealistic rather than profit-oriented positions. We also present new collective actions, innovative approaches to sharing space, architecture, experience, knowledge, data and collective histories in Central Europe.

Could you give an example of an ideal or collective use of sharing?

In Central Europe, before 1989 the “socialist space” was collective: everything belonged to everybody. To a certain degree this also meant that nobody cared because it was public common good. There wasn’t even a proper definition of the term “public space” as there was no “private space” defined either. After 1989, the situation changed. People were again allowed to possess private property and eventually started to take care of their own private space. Yet we still face a great deal of neglect of public urban space because the post-socialist society is not used to taking care of it. This is something that needs to be relearned: if people don’t stand up for their public space it will be taken by private space and companies.

Would you say that the legacy of a centrally organized culture in Central Europe still influences urban activism and attitudes to sharing in the region?

The older generation caries this legacy of ambivalent memories. On the one hand everything was sort of state-owned, on the other, there was a greater deal of socialist state propaganda which dealt with collective actions like the 1st of May celebrations, mass exercising like the Spartakiad or a collective women’s day. Still, when you speak to this generation, they have good memories as they felt a sense of community and feel that today there is less time for the exchange of ideas in a neighbourhood as everybody takes care of themselves and their personal profit. So, the older generation is happy to remember the sense of community they’ve enjoyed before 1989 but they have also bad memories of a forced culture of sharing.

The Interview took place in 09/19.

////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////

See also:

Sneak Preview of Shared Cities Atlas

"DOES EVERYTHING ALWAYS HAVE TO BE ASSESSED?" No. But when cultural work is financed with public funds, there is a necessity to evaluate.

Prague Permanent link

The one-day programme was based on discussion formats with renowned European architecture theorists, curators and urban researchers.

Prague Permanent link

Within Shared Cities: Creative Momentum the Czech Centres realized the "Iconic Ruins?" exhibition and an economic impact evaluation of the project. How does the future of the exhibition look like? What are the benefits of having an economic analysis of the project? Find the answers in the interview with Ivana Černá and Sandra Karácsony from the Czech Centres / Česká Centra in Prague, Czech Republic.

Prague Permanent link