How Culture Works

"DOES EVERYTHING ALWAYS HAVE TO BE ASSESSED?" No. But when cultural work is financed with public funds, there is a necessity to evaluate.

Prague Permanent linkIconic Ruins are high quality architecture that lost their ideological and programmatic meaning, and have become a modern-day ruin. What are the biggest challenges you face when dealing with these buildings? And what are the most distinguishing features, and opportunities for the Iconic Ruins? Find the answer in the interview with Vít Halada from the Academy of Fine Arts and Design in Bratislava, Slovakia.

©Anna Pleslová

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

By Kamil Pavelka

Let’s take it from the beginning – why Iconic Ruins?

At the time we were approached by Milota (Milota Sidorová, Ed. note) to consider participation in the project we were a bit skeptical to bottom up activist projects in the public space, considering them too weak to change something, too animated to survive without enthusiastic support, too spontaneous to have long lasting effects, too programmatic to define space. We proposed another expertise that we as architects and educational institution try to develop and that is to generate ideas that thrive for new spatial organizations rather than programmatic usage of existing spaces.

We had a history at the Department of Architecture dealing with late modern socialist architectures in Bratislava and Prague and we saw them as a tempting available research material to test their qualities and potentials to be transformed into nowadays needs. They were built in an era that tried, in its ideology, to be for all or to be shared among many. As this, they were cultural and institutional palaces with generous and quality interiors, well designed an extensive public spaces, set in prominent urban locations. However they became obsolete or underused during the last 30 years and therefore sort of residual spaces in the city fabric, ruins of former representative image and landscapes of unused square meters. As they are not as attractive and easy to refurbish as romantic industrial brownfields they were for a long time also not on developer’s radar, until recently. So we saw the opportunity to introduce their qualities into the ideological city planning process and show that they deserve to be shared again – not only as trendy settings to urban markets and community gardening but as liveable, walkable and usable public buildings.

Are there any impacts you would be looking for?

As we are an educational institution the impact we are always trying to have is on the students to show them actual thinking and producing of architecture. Another would be the will not to lose our position as experts on understanding and production of space to non-architects by showing our ability to generate ideas on possible futures of problematic buildings and spaces. Third one would be to show Iconic Ruins or late modern -socialist- buildings as high quality that could be acknowledged and accepted as relevant layer in the city and thus become part of future possible thinking.

© Anna Pleslová

The buildings have a common denominator of being an “Iconic Ruin”. They are however very diverse in their origin and original purpose. How do you work with these diverse buildings and their different goals?

I would say they are not that diverse from our point of view. We have tried to identify their common qualities to establish them as a sample group for testing different architectural strategies with student’s proposals.

I would say common for them are prominent location in the city fabric, generous public space around / under, or on them, then a generous interior, public spaces, exceptional or specific form and materiality. They do however differ in what program they were meant to cover but as this was a category that by proclaiming them ruins was not relevant for us we were able to test them on different new usages

What are the biggest challenges you face when dealing with the Iconic Ruins? Is it the developers, or public, or excessive protection by any chance?

I would say it could be all of them, but mostly in a negative way. The developers, I would say don’t see profit in dealing with them as they are specific structures and functions, so they are not easy and profitable to rebuild and it is easier to demolish them. The public until recently saw in them the communist ideology and thus they were labelled monstrous and ugly and they should be erased from our cities and memory. And for protection they are too young to be dealt with. I’ve read a methodology for preservation of specific city lately and the material considered everything built after the wars as a mistake that should be corrected – so the idea would be to have cities in the 21st century mummified 100 years old.

So the challenge would be to show that the buildings are architecture of high quality – comparable – with international examples and as such it deserves to be dealt with – moneywise. They are worth to invest and to look for solutions that could be profitable. They are worth to be visited and used again as they were designed for people – under a different ideology – but still for people – and a lot of them, to meet, to enjoy culture, to experience spaces where the society and culture could be performed. And they are worth to name their qualities, be aware of them and consider them as relevant part of our history, and not as mistakes.

© Stefanie Heublein

Based on your research, what are the most distinguishing features, and opportunities for the Iconic Ruins? Do you see any potential for their development?

Some clues are already in the answers above. But I’ll try to sum them up. First of all they are located in prominent spaces in the city and therefor they are targeted by the developers as they are very valuable building sites. But the sites are already also developed as generous public spaces and as so they introduced into the old historic cities another type of urban voids – semi covered passages or alleyways, piazzas, covered spaces or terraces. And these are overlooked right and not used now. Another feature would be their ability to be public also in their interiors – with their grand foyers, public concert, exhibition or congress halls. Such spaces are not part of nowadays buildings as they are not sellable or rentable. I would also say they were strategic cultural and societal infrastructures and as such they could serve again. For example Istropolis in Bratislava is the only congress hall with a capacity over 1000 seats, if you destroy it right now it will take a long time and x times more money to build a new one.

Are there any reactions to your work from the owners of the properties you research? Did you suggest anything to the owners?

During the project we came into contact with either institutions that are occupying the building, or own it or do try to find ways how to deal with them. In Katowice Miasto Ogrodow is responsible for the Dezember Palais, we showed the municipality of Trnava quick visualisations of possible rebuilding scenarios for the cinema Hviezda. We’ve shown to the city development office of Belgrade the possible scenarios for Bezistan revitalization, and we were in contact with the developer owning the Istropolis building. However it didn’t go beyond these initial meetings and presentations. I would say we as an academic institution are not really able to facilitate further process, but we hope it helped or started certain ways how these buildings are perceived by their owners.

What did you learn about approaching different types of institutions currently owning the buildings – have they been welcoming you?

They didn’t refuse us. We showed them a perspective that’s not easy to realize. I would say we tried to communicate to all of them that these building are worth to deal with, and proposed to them our initial ideas of how to do that from architectural point of view. I would say our views were welcomed but I am unable to say if it was relevant to them, but that was not really our goal to convince someone. Our goal was to present the possibility. We do understand that their decisions are made according to many parameters and our peculiar interest is only one of them. But I think there will be other voices or pressures will accumulate, and in the end could move the decisions to keep, transform or rebuild Iconic Ruins and probably the idea that it is possible will be already there. And we as an academic institution aim for preparing more of our students to be ready – future architects, municipality clerks, project leaders for developers who would be able to propose more specific solutions at the right time.

Interview took place at 12/06/19

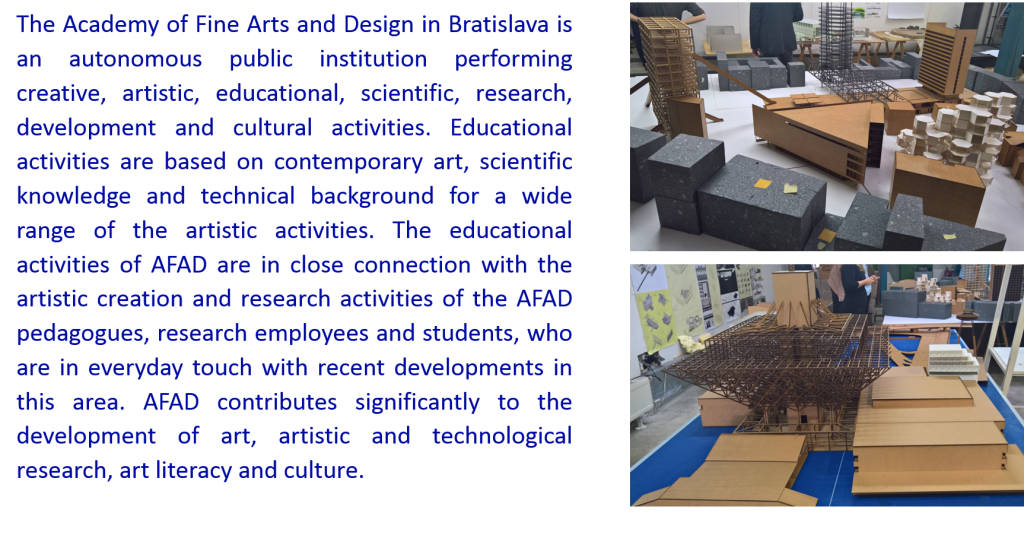

Model of Iconic Ruins © Anna Pleslová

See also:

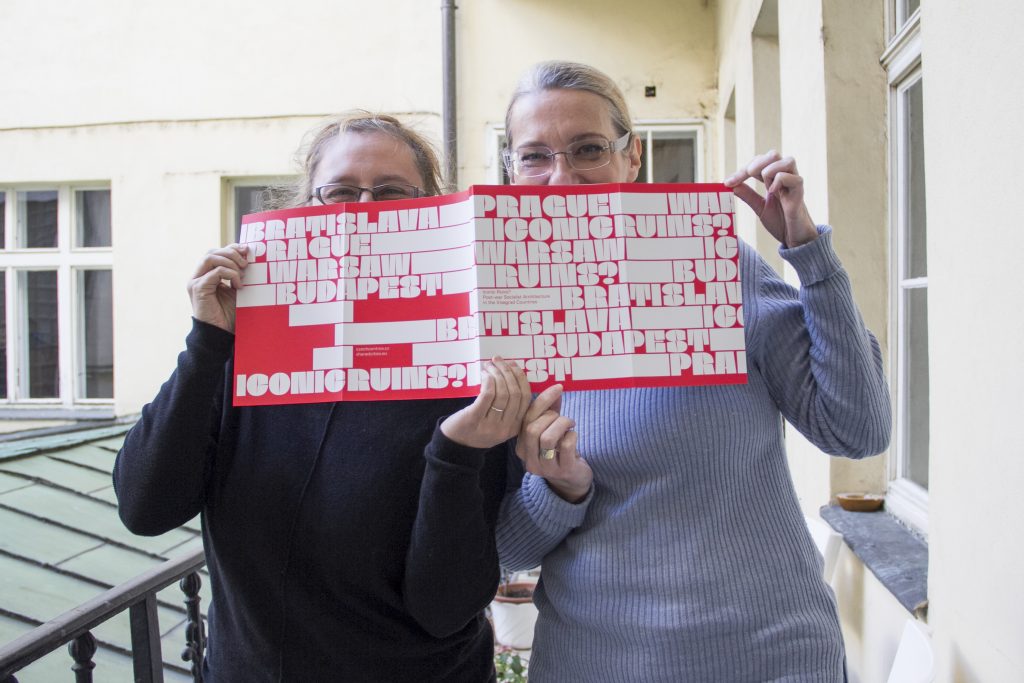

See pictures from the Shared Cities Ideas Yard: ICONIC RUINS?

VŠVU: Iconic Ruins / Strategies

"DOES EVERYTHING ALWAYS HAVE TO BE ASSESSED?" No. But when cultural work is financed with public funds, there is a necessity to evaluate.

Prague Permanent link

The one-day programme was based on discussion formats with renowned European architecture theorists, curators and urban researchers.

Prague Permanent link

Within Shared Cities: Creative Momentum the Czech Centres realized the "Iconic Ruins?" exhibition and an economic impact evaluation of the project. How does the future of the exhibition look like? What are the benefits of having an economic analysis of the project? Find the answers in the interview with Ivana Černá and Sandra Karácsony from the Czech Centres / Česká Centra in Prague, Czech Republic.

Prague Permanent link