How Culture Works

"DOES EVERYTHING ALWAYS HAVE TO BE ASSESSED?" No. But when cultural work is financed with public funds, there is a necessity to evaluate.

Prague Permanent linkTo embrace sustainable sharing economy requires re-imagining of many fundamental aspects of our society. Take for example the current nuclear family model - world-wide, it is the basis for our housing systems. And it is rather outdated.

Siemaszko Zbyszko ©National Digital Archive

Is there anything specific about sharing in post-communist countries that distinguishes it from any regional counterparts?

What is distinctive is the experience of state socialism which was based on the idea of sharing economy – as well as an economy based on labor. The state did not eliminate capitalist institutions outright, but instead they put them to a different use. As a result, they never fully abolished money or private property, only subjugating them to the moral principles of user value.

At the same time, socialism introduced the idea of “social property” (mienie uspołecznione)…

And it became an integral part of society. A week ago, I was walking through the Praga district in Warsaw. There, a monument is situated next to an old tenement building with a plate remembering a woman who died while defending “social property”. She was a shop assistant and probably died defending the goods in the store from a robbery, and the plate itself was paid for by the residents, not the government. Today, people would laugh at the idea of dying for a store’s inventory, but in the beginning of communism, this idea and devotion was wide-spread and celebrated.

Similarly, the entire cooperative housing movement in the 1950s and 60s began at the grassroots level though not many outside the region realize this. It was only recaptured by the state in later decades; by then, everybody had forgotten about the meaning and purpose of common property.

Around 1955, the state recognized that there was a huge housing shortage; this was due to the massive economic disaster which was WWII and the government’s subsequent investment in industry necessary to spur the economy. However, the young people who moved from the countryside to the cities to work in the developing industries demanded apartments, the lack of which saw an increase in hooliganism as well as other types of “unruly behavior”, a major urban problem in the early 50s.

That being said, communist Poland was not an Orwellian state – they didn’t have massive state capacities, so they were forced to mobilize all possible resources. The original plan was for enterprises and factories to finance the building of new houses, but that turned out not to be enough for the needs of the growing urban communities. At some point, people had to get involved themselves, e.g. through establishing housing cooperatives. This was also translated into a massive school-building effort which created the so-called szkoły tysiąclecia: thousands and thousands of buildings were built together by the people.

What did the process of forming urban communities look like in the first years of People’s Republic of Poland?

Well, in 1937, a few million peasants stopped sending food to the cities for ten days in the biggest agricultural strike in the history of Poland. The countryside was extremely poor, and they wanted to receive a fair share of the national economy. Of course, this revolt was brutally crushed. If you look into archives, you can quickly realize that the secret services of the police were really worried that these people are going to start a revolution.

Moreover, the country-side was well-organized and very strong politically. They equated sharing with a completely different moral economy than the city elites, eventually though these were the same young people who later moved to cities, and they brought this ethic along with them.

They adapted to the new reality very quickly, falling in love with the cities. There is a spurious argument that it takes generations for rural workers to adjust to urban life. It’s complete nonsense: in reality, this happened very quickly, and these people created a new urban culture.

Under communism, sharing was also a necessity especially in face of economic scarcity. How did it influence society?

There was a belief in the moral economy that, essentially, the society should be equal. In capitalist societies, life is organized around market distribution, where money is the universal medium. Under socialism, people had to create these ideological fulcrums as it had never been fully practiced before. People had to find a replacement for the institution of “contacts” (znajomości), an informal network of connections to people which ultimately served as a way of getting things done. As always, there were both benefits and downsides to this societal shift.

The vacuum that was left by the market was quickly filled by a number of different institutions or social practices, for instance – the queue. We often forget that it is one of the most democratic institutions; you have to wait your turn. In communism, queue committees were formed at the grassroots level. After all, there was no queue in the countryside!

© Siemaszko-Zbyszko, National Digital Archive

One of the most symbolic examples of everyday sharing was television – sharing one TV set among neighbors in one block of flats.

Exactly, the experience of watching TV together is a great example. Even more impressive is that people collectively raised money to buy transmission equipment, so they could send/receive transmission signals in Łódź and Katowice. For example, a lot of effort was spent in Łódź in order to create local channels, a form of common property, but they were eventually nationalized and taken over by Warsaw. Seeing their toil reappropriated angered many people, and they weren’t alone.

Neighborhood associations – which were very important in blocks of flats and the newly created housing estates – as well as other networks of trust began to flounder in the 1980s. Until then, the people had been quite innovative in their use of property. Furthermore, it was considered bad taste to keep something for yourself. Instead, if you had something, it was expected that you should share it with others, and people actually enjoyed doing it.

Nevertheless, state socialism in Poland was an aborted revolution. For instance, in the countryside, collectivization was a failed project; it required a strong government to reinforce the it, and this was non-existent. Coupled with the fact that serfdom was abolished serfdom a century before, and there were few families who had any real or perceived – private or collective – property to go back to.

Related to this is the social phenomenon of “peasant individualism”; a recent development that people attribute to the boom in urban gated communities. Many Central and Eastern European cities love to fence, divide, and separate themselves from the rest of their community, a manifestation of rigid individualism. Finally getting what their families had wanted to acquire for generations has led to the near obsession with private ownership.

It is fascinating that these two dimensions coexist at the same time: sharing and dividing.

In today’s post-communist societies, there is a very strong feeling of individualism. We may even call it “the cult of individual property”. Periodically, there are moments in history when some traditions are amplified by external situations. When the regime was ostensibly pro-social, all of these more social traditions were magnified. Then, with the crawling neoliberalism, these more individual inclinations began to surface. Today it has become grotesque – trust in society, in your community, has almost been completely wiped out.

There was also a strong effort put into popularizing common, participatory work in cities. People worked together to build these new urban realities.

That came from the idea that you have to do things together because the city itself is a kind of common, social property. Another example are land use violations and the erection of unpermitted buildings.

Although it is often burdened with pejorative meaning, under communism, especially in the 1970s, there were thousands of self-taught builders who erected whole neighborhoods. Often it came down to two brothers-in-law helping each other to build a house for their families. You can still see some of those houses today, especially on the fringes of cities; aesthetically, they are pretty terrible and badly constructed.

The same goes for the mass phenomenon of collective church building in the 1980s. Architects were very annoyed that they didn’t have the last say in how these temples were going to take form. I remember my grandfather was part of a movement – a network of people distributing goods from the West which came to Poland via the Catholic Church, mostly clothes, sweets, and food, which was another layer of the sharing economy.

Are these grassroots traditions of collective house-building in any way present in today’s society in Poland?

When I started doing research in Poznań on local urban movements, I quickly realized that there is a strong connection between those tradition of autonomous house-building and these new emerging urban activists. It became clear that this early 21st century eruption of urban movements in Poland was in fact a late blossoming of these urbanites from the 1970s and 80s. The social capital, so to say, actually survived as a neighborhood bond and became politically productive in later decades.

When you look at the results of the local election in 2010, the results were very uneven in Poznań. A newly established urban activists’ political party called “My-Poznaniacy” on average gained 10% of the votes, but in some places the support was much bigger, even reaching 20%. The strongholds were exactly the same places where there had been a concentration of self-constructed houses.

What do you think about the growing popularity of sharing economy?

It has little to do with actual sharing. Of course, it can be something exciting, a current buzz phrase for people who were brought up in the neoliberal era. But of course, on many other levels, this is not something completely new. There was always some kind of sharing economy, but it was never sexy from the point of view of marketing. If you look at Detroit, urban gardening is only a fraction of the city’s economy. This is an African-American city that for the last fifty years has been devastated by Wall Street and racism. A few middle-class hipsters who are turning empty lots into urban gardens are not going to bring structural change to this community.

Non-Western cities always had some kind of urban gardening. For example, in Russia a huge percentage of food is still produced in urban farms. The same goes for Hong-Kong or Havana. People have been doing it for years – perhaps they had a different name for it, but in the past, nobody was looking for a way to change it into a cool marketing campaign.

Still, do you think countries in our region will buy into this fad?

In Poland, there has always been this idea that we lack resources, that life is difficult, and this forces us to share different commodities. Any trend should always be translated into our own experience, but yes, this movement feels intuitively linked to our region, whether or not it will work is another thing. The Polish anthropologist, Tomasz Rakowski, wrote about the contemporary practice of “splitting up” (rozdrabnianie). A few families get together and buy one chicken in a supermarket, and then divide it into smaller parts because it’s much cheaper than buying individual segments. There is nothing cool or hip about it; it is how poor people manage to survive.

Sharing economy practices seem to be gaining popularity especially in the United States and in Western Europe. What effect do you think this will have on these societies?

Recently in Sweden the government began to subsidize maintenance. If you have a washing machine and it breaks, normally you buy a new one, but now the government pays you to repair it. Perhaps Swedes need this kind of training to encourage mending rather than replacing things.

To really embrace a sustainable sharing economy will require a reimagining of many fundamental aspects of our society. Take, for example, the current nuclear family model; it is the basis for our entire, world-wide, housing system, and it is quite outdated. In the Netherlands, as well as elsewhere, there are interesting experiments being done combining student dorms and pensioner apartments. The intention is to teach people how to share between generations, and this could lead to numerous, unforeseen benefits.

The West is starting to catch up; however, this is the first time in quite a while when the younger generation will not be better off than their parents. For them, the idea of constant growth and economic progress is over. Western societies will be forced to learn how to maintain and share things; you can prepare for this eventuality or have it thrust upon you, either way this is going to be the future.

© Siemaszko-Zbyszko, National Digital Archive

author: Jędrzej Burszta

Kacper Pobłocki holds a PhD in Sociology and Social Anthropology from Central European University. He is also a graduate of University College Utrecht and was a visiting fellow at The Center for Place, Culture and Politics at CUNY (directed by David Harvey). He published on urban movements, class and uneven development in East and Central Europe in a number of edited volumes and journals (e.g. in Critique of Anthropology or Polish Sociological Review). His dissertation “The Cunning of Class: Urbanization of Inequality in Post-War Poland” won the Polish Prime Minister’s Award for Outstanding Dissertations. Actively involved in Polish and Central European urban activism from their very onset. He was the co-organizer of the first national Congress of Urban Movements in 2011 and he co-authored a legal manual for urban activists titled “A guide for the helpless: practicing the right to the city” (2013). Currently he is working on a book manuscript that will analyze the relationship between global economic shifts and trajectories of urbanization in Poland.

"DOES EVERYTHING ALWAYS HAVE TO BE ASSESSED?" No. But when cultural work is financed with public funds, there is a necessity to evaluate.

Prague Permanent link

The one-day programme was based on discussion formats with renowned European architecture theorists, curators and urban researchers.

Prague Permanent link

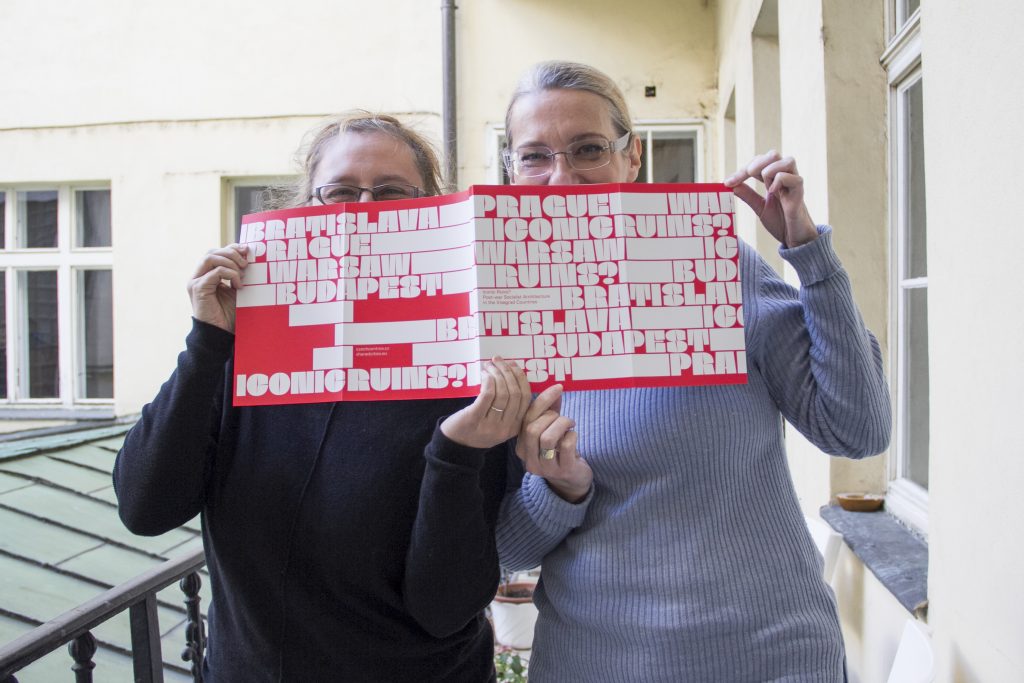

Within Shared Cities: Creative Momentum the Czech Centres realized the "Iconic Ruins?" exhibition and an economic impact evaluation of the project. How does the future of the exhibition look like? What are the benefits of having an economic analysis of the project? Find the answers in the interview with Ivana Černá and Sandra Karácsony from the Czech Centres / Česká Centra in Prague, Czech Republic.

Prague Permanent link